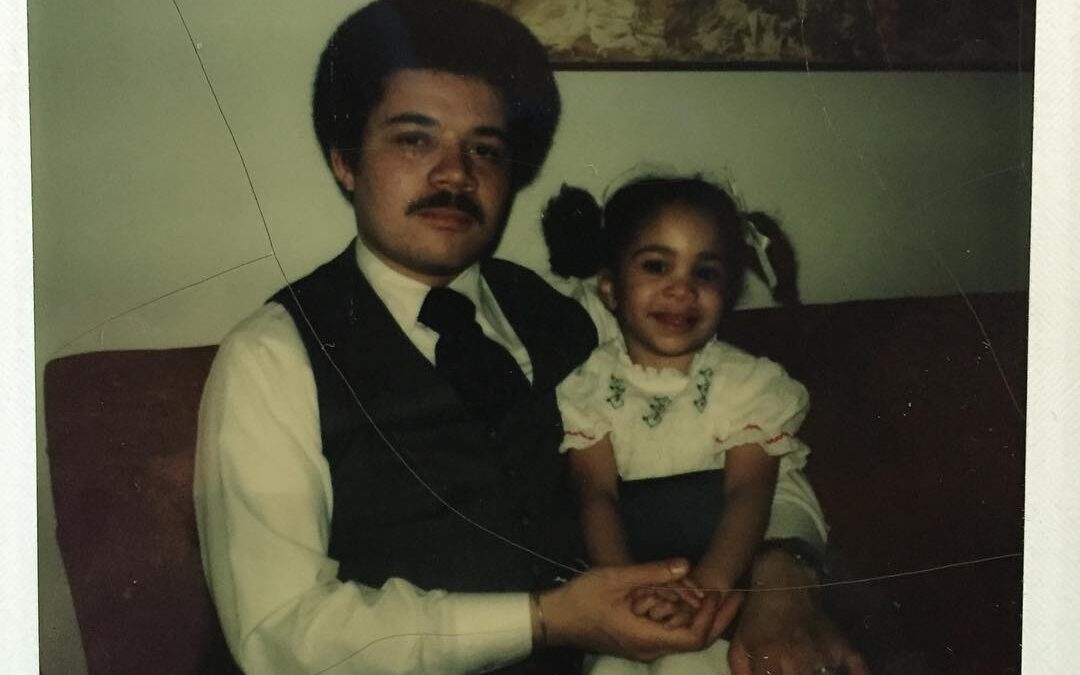

He called too early in the morning. Every year on my birthday. My father called to tell me happy birthday. And to tell me that he held me first.

“We saw that your hair was black. And I held you first.”

“I know Daddy.”

This year marks ten years since my father died. He was too young, but, like so many other things, he did it his way. Alone. At home. With his paperwork and business in place.

I don’t miss my father. My father and I had a complicated relationship. He was a functional alcoholic who became so naturally mean that he could say demeaning and hurtful things after just ten minutes of phone conversation. Constant fear seeped from the walls if Daddy was home. I lied every time I said I loved him. He was also a repository of black history who believed deeply in providing for his family and giving back to the local community. He was generous with hugs, even if gruff with his voice. He wanted to shield me from the pains of colorism, racism and poverty. He believed that a long walk and talk with God would solve most problems. He wanted to be better than his father.

I knew that they hated Granddaddy. I knew his children didn’t want to be around him, and Nana had no good words for him. I saw him eat stacks of Wonder bread with dinner while Mama whispered, “Pops will be good around her.” My grandfather was a handsome lean brown man with salt and pepper hair, best described in a southern tone as “a tall drink of water.” Granddaddy smelled like stale cigarettes, and he held my hand when he took me on the subways around DC. He lifted me high to see the sights on the Capitol Lawn at Christmas time, and he sent me red and green velour v-neck sweaters for Christmas. I laid my sleeping body across his chest in the backyard of a North Carolina cousin during my third summer.

Daddy and I ended well. Years of therapy helped me to see the complex person my father was. I spoke my truth once and forgave without apology. I developed boundaries that allowed us to interact without debasing the personhood I had fought for. We were able to laugh and dance together. In his last year, he had many moments of kindness and largesse with me. I didn’t need it, but I considered it a gift of grace.

In his last living year, he asked for grandchildren. He wanted to be a granddaddy.

My daughter would not be born for another five years. I didn’t even know her father when my father died.

He would have adored her. He would have noticed how her chin and pinky fingers look like our family’s. He would have fussed while making her vegan baby food. He would have recited his grandfather’s poetry to her. He would have crawled around on the floor with her, and read her books to sleep. He would have laid her tiny sleeping body across his stomach while watching television. He would have bragged on the loquacious intelligent girl she is becoming.

I don’t miss my father. I had more than thirty good and bad years with him. I deeply miss the grandfather he would have been. I ache that my daughter only knows him through stories and pictures. I bemoan the belly hugs and Cherokee rhymes she misses out on. I hate that she lost a Granddaddy only I know exists.

I tell her about him. That my freckles come from him. That he asked about her. That he looks out for her even now. As an ancestor. I tell her that people don’t always deal with pain in healthy ways. I tell her that love is deep and complex. I tell her about our heritage.

So I amble through the refrigerator section of the grocery store looking for pork bacon. I buy Welch’s grape jelly. I scramble eggs. I tell my daughter about the “Coleman egg sandwich” Grandddaddy would have tried to make for her (hopefully a vegan version) and we remember what has been lost and what would have been.