I was instantly nauseous. My stomach turned in knots and I doubled over. I collapsed into my seat and held to the edges.

I became sick. Literally.

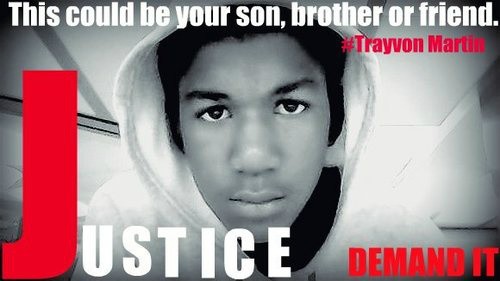

This was my response to hearing the news of the verdict in the trial against George Zimmerman for the murder of Trayvon Martin.

In the hours and days that followed, my African American friends and I expressed similar feelings: paralysis, anxiety, despair, outrage. From the rallies immediately following the verdict to the varied posts in social media outlets, the wider world is witnessing the collective anguish of African Americans.

The verdict causes many African Americans to feel as though justice has been denied once again. There are historical roots to this case dating to the similar murder and trial of Emmett Till, countless lynchings, beating and arrests to the contemporary unequal application of legal force and action with Marissa Alexander. I see and feel anger and disappointment.

I also experience the collective pain and sadness of African Americans as we struggle to raise and guide our children in a society that gives so little value to their lives. My colleague Valerie Bridgeman calls this “black mama trauma.” That we have done this for generations does not ease the task. Rather, it renders heavier the role.

Like many others, I blindly groped my way to church the next morning. I confess. I didn’t go for theological reflections on injustice, or because there is some ingredient in my faith that allows me to trust God in the midst of great challenge. I went to church for the community of other anguished souls. I went to stand shoulder to shoulder and hand in hand with other African Americans who were as ill and spent and disappointed as I was.

I saw black church after black church in my community talk about what happened with Trayvon Martin. We lamented, protested and talked. We came together declaring that something had to be done. Our faith demanded it.

For decades, the psychologist Na’im Akbar has discussed the ways in which slavery and its legacy of racism have damaged the psyches of African Americans. As I witness the mass outcry of black pain, I am reminded of this particular challenge to African American mental health.

It’s eerily coincidental that the pain of African Americans should become so public during July, designated Bebe Moore Campbell Minority Mental Health Awareness Month by the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI). As we are called to end the stigma against mental health in minority communities, I realize that black churches know how to respond to collective despair.

I imagine a time when black church folk come together with urgency around mental health challenges among African Americans. We could talk with community changers and wail about the difficulty of our experiences. More importantly, the response to the verdict reminds me that faith-motivated protest is not reserved for acts of racial and political injustice.

Protest may be an appropriate response to our individual pains and despairs. This is what the biblical character of Job does when he protests to God about the pains of his life. These protesting black churches are teaching me that we can protest around issues of mental health. Churches can protest the stigmas that create silence and shame. We can protest unequal access to mental health services. We can protest the stresses, fears and traumas that chip away at our mental wellness. As Christians, we can protest our own words and attitudes that exclude anyone from love and acceptance. Our faith demands it.

I believe it starts in small ways. This protest may well start with the blind groping to a place of solidarity where our pain is recognized and shared.