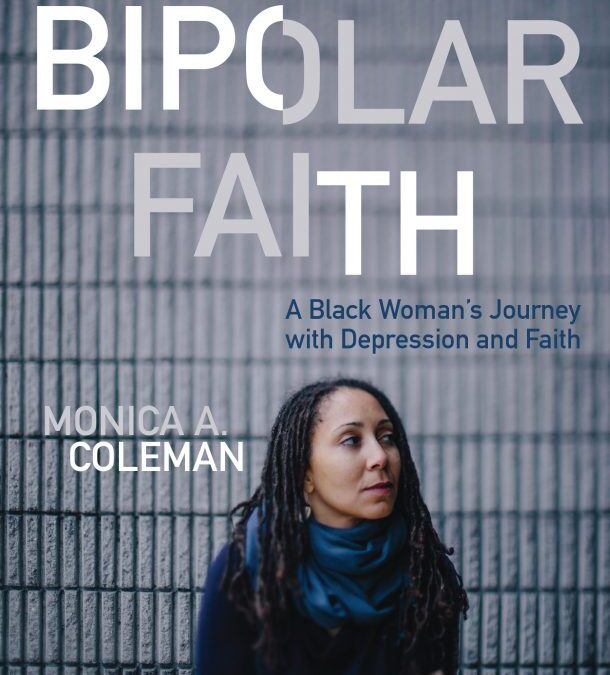

Syndicate has commissioned this amazing series of reviews of my book BIPOLAR FAITH! I’m blown away by the attention my colleagues have given to my work. Roberto Sirvent introduces the series here:

My mother has dealt with chronic migraines for almost thirty years now. It’s an everyday occurrence, well at least almost every day. I know because we talk on the phone on a daily basis. Family and friends, with the best of intentions, plead for her to get up. To go out. To do something. She has to convince them that she can’t. She really can’t. My mom has even told me a few times that her morning headache was so bad, so debilitating, so terrifying, that she thought “that was it” for her.

This “it” that my mom speaks of is a kind of “death-threatening pain” that theologian Monica Coleman describes in a 2011 online interview. Discussing the stigma around mental health for many black people, Coleman recounts the following story:

In the midst of a depressive episode, I had a friend say to me, “We are the descendants of those who survived the Middle Passage and slavery. Whatever you’re going through cannot be that bad.” I was so hurt and angry by that statement. No, depression isn’t human trafficking, genocide or slavery, but it is real death-threatening pain to me. And of course, there are those who did not survive those travesties. But that comment just made me feel small and selfish and far worse than before. It made me wish I had never said anything at all.

My mom can resonate with this guilt, a guilt that piles on after listening to such overpowering voices. She wants to give up. She’s tried every medicine, every cure. She’s probably seen every neurologist in Scottsdale. She even visited an acupuncturist who was featured in her favorite morning news show. Having been a faithful and devoted Catholic all her life, she gets frustrated because she thinks God is frustrated. Frustrated at her. For what, you ask? For not being able to get out of bed. For not being able to do something, anything. For being “useless.” Yes, she has her “good days,” those days that allow her to play with her grandchildren. But these days are rare. And then she feels pressure to feel grateful for the good in her life, similar to what Coleman describes above. “Other people have it much worse,” my mom constantly tells me. “Why am I complaining?”

Monica Coleman’s book Bipolar Faith: A Black Woman’s Journey with Depression and Faith is written for people like my mom. By this, I don’t just mean for my mom’s intellectual stimulation, but for my mom’s survival kit. It’s written so my mom can keep going. My mom’s reaction to Coleman’s writing is similar to my students’ when I first assigned Bipolar Faith to them a couple years ago. There was no light bulb that went off, no revolutionary insight that blew their minds. The effect was much more meaningful, more profound than a library of dissertations on the subject. In Coleman’s stories, her words, and her brilliance, my mom and my students found a companion. A companion for an unsteady, uncertain, and scary journey. I’ve never been one to think that a book can change the world. But what I do know is that Bipolar Faith has made my mom’s world a little less lonely.

In the symposium’s first essay, Thelathia “Nikki” Young reads Bipolar Faith as an invitation for people of the black diaspora “to live beyond, not despite, the generational inheritance and tangible effects of individual and collective grief, depression, and trauma.” Praising Coleman’s ability to produce what Audre Lorde called “erotic knowledge,” Young focuses on the book’s call for both a radical honesty towards and a radical refusal of death. “This refusal,” Young writes, “seems to mean . . . developing life-saving rituals.” Young concludes her essay by highlighting Coleman’s “meaning-making map of survival,” and she “honor[s] the ways that Coleman chases livability by navigating the refusal of death.”

The symposium’s second essay features Lisa Powell’s reading of Bipolar Faith, where she explores what these life-saving rituals look like in the context of a white, male, heterosexual world of academia. In a context “surrounded by a disproportionate number of men, taught by men, reading only men,” Powell writes, “it’s no wonder women sometimes become sick.” She finds in Coleman’s work an outlet for which to address the many ways that higher education causes anxiety, stress, and mental illness, but also beats down people with illness (especially as it intersects with one’s race, gender, and sexuality). This includes not being taken seriously as an academic, suffering from an imposter syndrome, and having one’s work rejected for not being “real” systematic theology. “We enter a program of study in service to God, and surrender ourselves to the parameters and criteria of the discipline, but upon entering, find it antagonistic to our perspectives, experiences, and ways of being,” Powell observes. “How do our bodies, our selves, and our faith survive?”

Melanie Webb, in our third essay, draws on Augustine’s Confessions to show how Coleman “exhibits an Augustinian openness to narrative potential” yet rooted in a vastly different confessional tradition—namely that of process theology. Throughout her reflection, Webb uses Augustine and W. E. B. Du Bois to help us understand how artfully Coleman sets up her narrative, even and especially the narrative of her rape. To be sure, what Coleman says matters a lot to Webb, but Webb pays much more attention to how she says it—how, in other words, Coleman “lets her soul speak.” “And as Augustine relies on psalms, so Coleman relies on hymns and spirituals,” Webb writes. “She uses the language passed down by her mother and grandmother; she makes a world with these words.”

In the symposium’s fourth and final essay, John Swinton centers on the recurring theme of diagnosis found in Bipolar Faith. He finds in Coleman’s narrative an account of her “being diagnosed—both by the church and by medicine.” Throughout his response, Swinton addresses the hermeneutical challenges raised by both medial and theological diagnoses. One of the many virtues of Coleman’s writing, Swinton notes, is that she shows how these diagnoses might “be necessary for certain purposes, but they are clearly not sufficient.” After chronicling how “medical imperialism” serves as a sort of epistemic injustice against many patients, Swinton shows how various theodicies play a similar role in religious spaces. Because Coleman resists such imperial and reductionist explanations, he concludes, Bipolar Faith invites both the church and medicine “to listen differently and to hear more faithfully.”

Originally published here